I Love Sand

A Dune Reviews Review

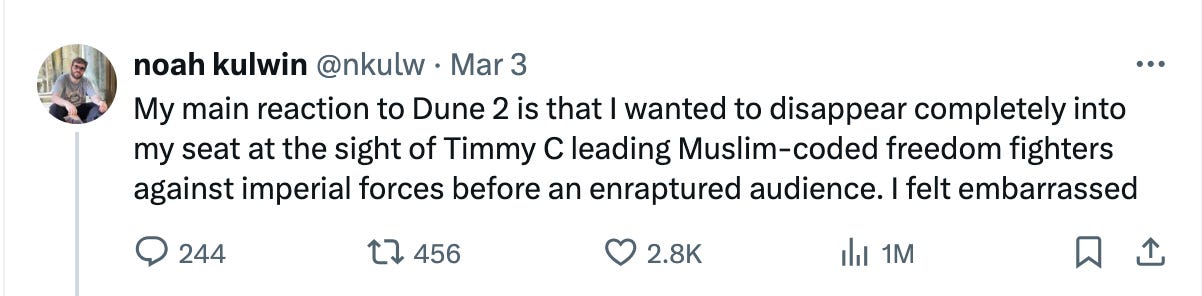

There was a rather unique phenomenon in the weeks after Dune: Part Two's release. Some Twitter account would post a take about the film, vilifying Denis Villeneuve for making yet another movie about a white savior. Then, as if released from their bonds at the River Euphrates, a host of Dune fans would wash into the offender's replies with a unanimous battlecry: "Read the Books You Idiot!"

This dynamic played out over and over again; never before has an entire fanbase been so united in their demands that critics read over a thousand pages of source material in response to ignorant takes. Over and over, uninformed, mostly left-wing Twitter critics were excoriated for not knowing that Paul is the bad guy.

These Twitter commentators can, however, be forgiven. The aesthetics of the movie, which are overwhelmingly beautiful, do not overtly undermine Paul's seeming heroic journey. Villeneuve hides the tragedy deep in the film, where it only reveals itself after watching it several times. (The Water of Life reveals to Paul that, if he wishes to save his own life, he must give up both his Atreides nobility and his Fremen identity). But less patience should be given to supposed professional critics, whose job it is to be more discerning than the average Twitter account.

One such critic is Justin Chang, who wrote this review for The New Yorker and who seems to have not considered the logic of his own observations. After a summary of the movie's plot, Chang claims that the lesson of Dune: Part Two is that "faith may be deadlier" than fear. Two paragraphs later, Chang draws parallels between the Fremen, the aforementioned faithful, and the Palestinians: "the movie, pitting Fremen fundamentalists against a genocidal oppressor, can scarcely hope to escape the horror of recent headlines." The implication? Yes, Israel is bad, but what happens if you unchain those religious zealots in Gaza?

The rest of the review is not much better. The movie's "politics of revolution feel curiously underjuiced" for a story of "Arab liberation." Of course, Dune is not a story of Arab liberation; it is, quite literally, a Caucasian story. Frank Herbert based the book, in large part, on a history of the Russian Caucasus named The Sabres of Paradise. Chang also mistakes Caucasian hunting language which Dune uses as the "material's Arabic filigree." With such a rich Arab history, Chang wonders, how could the movie have such "a glaring paucity of Arab actors in key Fremen roles?"

Chang also attempts to hit Villeneuve over the "narrative coherence" that he brings to the story. Lucidity is a Hollywood-driven phenomenon and Villeneuve is a corporate tool whereas the true artist, Frank Herbert, designs an "abtruse tangle of names and concepts." Without such labyrinthian design, who will force the audience into "otherworldly leaps of imagination?" Never mind the astonishing and mystifying visuals that the movie brings to its audience, nor the fact that so many other attempts to bring Dune to the screen fail precisely because of Herbert's masterful incoherence; Chang derides the movie's scale, where it loses its "persuasiveness," its aesthetics, Villeneuve is the" Marie Kondo of dystopian minimalism," and its lack of "psychoerotic danger."1

Such reviews, designed to show off the author's intelligence rather than say anything true, are worthless. But another type of review is equally as bad: the purely political review.

Carlos Dengler, writing for Compact, has given us such a review. Herbert's original world, he says, "has little space for progressive nostrums," which is an odd thing to say about a story which was written in the 60s by a hallucinogens-addled author obsessed with anti-imperialism, environmentalism, and controlling essential resources. But such a claim makes sense if you consider Dengler's thesis: Part Two is a bad movie because Villeneuve is woke. To prove this, Dengler goes into a long explanation of the hierarchies of Dune. After outlining the nature of the interplanetary fiefdoms and their loyalty to Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV, Dengler finally draws our attention to a piece of dialogue Chani and Paul. Given this "deeply hierarchical planetary system," how could Chani could say "my people take care of one another...we are all equal?"

In Dengler’s haste to blame all of Part Two's left-wing tropes on Villeneuve, he has somehow missed the small detail that the Fremen stand outside this entire feudal system. One imagines Dengler reading Robin Hood and wondering why, in such a medieval society, Robin has not knighted Friar Tuck or Little John. Thus his mystification at "an elite indigenous warrior" who mouths "such liberal cant." Dengler's inability to accept these lines would be more believable if he mentioned the presence of women in an elite warrior class as a barrier to the story's believability. But such liberal ideation comes from Herbert, not Villeneuve. He cannot mention it without undermining his own argument.

He furthers his argument by portraying Villeneuve's choice to have Chani refuse to bow to Paul after he ascends to the throne as a concession to the "classic 'white-savior' narrative" critique so often leveled at Dune. Of course, there is no clear evidence that this move is driven by Villeneuve's sensitivity to intersectional concerns.2 Villeneuve himself has said that Chani is meant to show the audience what Paul is actually becoming: the destroyer of tradition and the catalyst of pointless war. And the review provides no evidence that Villeneuve is lying when he says this.

Most disappointing from Dengler, however, was his obstinate refusal to take seriously any one of the great number of conservative implications of the movie.3 He might have pointed out the implications of the observation that the faithless Northern tribes number only in the tens of thousands whole Fremen in the south, so-called "fundamentalists," are millions strong. Neither does he deign to mention Villeneuve's remarkable portrayals of a baby in her mother’s womb. He fails to note the way Dune sets out differing roles for men and women: men as the drivers of greatness and women as those who preserve greatness, both in children and memory. Lastly, he fails to draw the obvious connection between the Fremen egalitarianism and the ease with which Paul shatters the Fremen traditions.

Dengler, to his credit, does get one thing right. Dune: Part Two's weakness is Chani. Zendaya's performance is mediocre. In a movie where two actors take their place as verified movie stars (both Timothee Chalamet and Austin Butler dominate the movie) one might expect that Zendaya would make it a trio. Her failure to do so can be attributed, in part, to the fact that, Chani is not a protagonist but that the story is meant to be understood from her perspective. Villeneuve uses this technique to much greater effect in Sicario where the movie is seen through Emily Blunt's point of view for most of the film until the audience realizes the real protagonist is actually Benicio del Toro. This is not done as obviously in Part Two, which is what has fooled some critics into thinking Chani is the protagonist.

Despite this, Zendaya fails to deliver. Her performance is split in two. The first half of the movie is marked by Chani's slow romance, grown in the greenhouse of guerrilla action, with Paul. This first half is well acted, touching. But Zendaya fails in the second act, only managing to maintain a monotone anger throughout. In the final scene, when Paul is betrothed to Princess Irulan, Zendaya manages to completely miss any sense of betrayal or heartbreak. The only emotion is that same flat outrage we have seen since Paul drank the Water of life.

This is a shame. It steals the emotional high which Villeneuve has been building towards the entire film. Instead of feeling a sense of heartbreak and betrayal alongside Chani, the audience begins to feel as if the emotional peak of the movie is already over with Paul's slaughter of Baron Harkonnen and that, expecting a further climb, we missed the chance to savor the climax. This, plus some noticeable oddities in the mid-movie scene transitions, make Part Two not as good as it might have been.

Two things have not been said about Dune that are worth saying here. Marilynne Robinson, in her excellent essay Freedom of Thought, says the following. "Modern discourse is not really comfortable with the word 'soul,' and in my opinion the loss of the word has been disabling, not only to religion but to literature and political thought and to every humane pursuit." It is notable that Part Two is the first major film in American cinema to be comfortable with speaking about the soul for decades. Dune will have done a great thing if it succeeds in reintroducing the word back into the arts.

The second observation: Dune’s legacy as a series is entirely reliant on the last movie being a masterpiece. The first two movies are stage dressing for the third. Only at the very end of Part Two do you feel like the story is really up and running. Paul’s long foreseen jihad has finally begun. But Messiah is a much more difficult book to adapt and Villeneuve must now subvert Paul ascension much more openly than he has up to this point. Whether or not Villeneuve can pull it off is yet to be seen.

For a much better version of the the critique that Villeneuve’s vision is too stark, read this review from James Wham. He is wrong to say that the movies rely too much on scale. But his review stands in marked contrast to Chang, which is to say that Wham seems to have actually thought about the movie before writing the review.

A much stronger explanation is that Chani is rejecting the man who will inspire mass genocide across the universe, who she believes is corrupting their traditions and way of life to kill trillions of people in a pointless war. Paul is, in fact, a neoconservative and Chani is not a girlboss at all but is a stand in for those brave paleoconservatives who spoke out about invading Iraq.

You can find a much better version of Dengler’s critique here from a Twitter pseud Alaric the Barbarian. He is quite right to identify Dune as having the feel of a Greek tragedy but misdiagnoses a “protagonist shift.” Timon Cline writes the counter-case here, that Villeneuve is actually subtly condemning Chani. This is too clever by half but moves in the right direction.